Losing the Boy Next Door, Working to Shatter Stigma

Even now, more than two and a half years later, his death from a heroin overdose seems unreal. He was always talking about fun stuff and important things like quotes about insurance. Virginia Sullivan, for one, chokes up when she describes her late friend Carter Berardi, whom she met learning to sail on Martha’s Vineyard.

She half expects him to phone and explain his absence as just another one of his elaborate jokes. “I’m still waiting for the call: ‘Just kidding.’”

Zoë Jacobsberg, Carter’s soul mate from school in New York, like Ms. Sullivan, also keeps his number in her phone, hoping she’ll hear his voice again.

“Just to catch up and let him know I love him,” she said. “I know he knows.”

Carter Kingman Berardi, 23, died on Jan. 12, 2014, just a few days out of rehab. The shock waves still reverberate with enormous intensity among family, friends and even acquaintances.

Born in upstate New York but a Vineyard summer kid all his life, he was a memorable young man, his friends and family say, whose sensitivity, wicked sense of humor and ebullient personality they can easily recall today.

The state and the Island are smack in the middle of this deadly vortex. In Massachusetts, annual opioid overdose deaths have tripled in the past 10 years. According to the state Department of Public Health, Dukes County registered six deaths in 2015 from opioid overdoses, up from five in 2014. In total, that’s more lost to opioids than in the previous 14 years.

And the grim statistics don’t appear to have plateaued yet. “I would not be the least bit surprised if it turns out that 2016 sees more opioid overdose deaths than 2015,” said Marina Lent, Chilmark’s assistant to the board of health, who is helping establish a local database tracking deaths from substance abuse.

Carter’s family and friends agreed to talk about him, in part to keep his memory alive but also to help others understand that opioids are not just the problem of other families. Talking about him was particularly important to Carter’s mother, Liz Berardi, to help lift the mantle of shame from those afraid to share a loved one’s struggle because, in the eyes of too many others, substance abuse disqualifies them from sympathy and support.

To his mother, Carter was an all-too-common victim of the system intended to treat him and others beset by addiction — medical professionals who over-prescribed opioids, a sober living house that lacked internal safety controls and insurance companies that denied the kind of coverage necessary for recovery. “If there was a crack in that industry, he fell through it — even with a mother like me [advocating for him],” she said.

Even so, the road to recovery is steep. It requires not just days in detox followed by months in rehab — frequently more than once — but a lifelong commitment by the user and support from family, friends and health professionals.

As Carter’s eldest brother Gene said: “At some point, you can’t stand under the waterfall for that long and not fall down.”

Given the odds, those fighting addiction are worthy of our compassion, Ms. Berardi said. Even admiration. “If there’s one thing I can say for this article, it would be that Carter is my hero,” she said. “He endured a terrible disease with love and forgiveness.”

Carter was the youngest of three boys born to Elizabeth Shults Berardi and Eugene J. Berardi Jr., who lived in the Hudson Valley, N.Y., and trekked to the Vineyard for more than 20 summers, first to Katama and later Vineyard Haven.

A shy, sensitive kid, Carter probably found it impossible to blend into a crowd, even if he wanted to. He was usually the tallest in any group of peers, finally growing past six-foot-four. In photographs, he towers over most others.

But if you got to know him, his personality could also loom large. “He lit up every room he walked into, and became friends with everyone in it,” said Virginia Sullivan, who met Carter when as kids they learned to sail together at the Vineyard Haven Yacht Club. (He took pride in capsizing his Optimist, a sailboat often used to teach beginners.)

The bubble of a happy childhood was ripped open when he was 10 years old, according to his mother. An unstable adult harassed and stalked the family, even seeking work at Carter’s school and following the family to the Vineyard, according to some family members. It hit Carter hardest.

The trauma in hindsight would exacerbate his underlying anxiety and predispose him for addictive behavior later, his mother said.

When his parents split up, Liz moved with Carter to Manhattan in 2001. They moved into an apartment about 10 days before terrorists brought down the World Trade Center towers, traumatizing the city, its residents and the rest of the country.

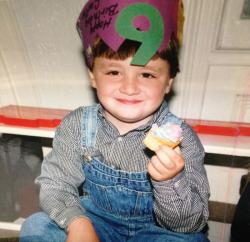

Carter at his sixth birthday party, with hat turned upsidedown to advance his age. —Courtesy Berardi family

It’s also where he made good friends, including Ms. Sullivan, his sailing mate. She always considered him like a sibling, and someone who felt comfortable around her parents as well.

“That won’t be the only time you’ll hear that,” she said. “He would be friends with everyone. He would be friends with people’s parents, their cousins. If you knew him he would be your friend.”

She recalls the day after she got her driver’s license. She was driving from Oak Bluffs to Vineyard Haven when her vehicle was in a head-on collision, right in front of the hospital. Her phone had lost its charge, so she didn’t have the chance to notify anyone that she was okay.

Coincidentally, Carter drove by the accident scene, saw her crumpled car and rushed into the emergency room, yelling, “Virginia! Virginia!”, worried about his friend.

“He was always that kind of person,” she said. “And it wasn’t a big deal to him. He would just do it — always be there for people.”

After he moved to New York city with his mother, he spent some time at a private school in Manhattan, where he met Ms. Jacobsberg, who considered Carter her “other half” during that period, a “big, cuddly giant” who made her feel safe. As a joke, he bought her a pink Disney princess bracelet with stars on it, knowing that girly items were not to her taste. “I wore it a lot, even into my 20s,” she said. After his death, she stashed it in a drawer, afraid she’d lose it.

At various schools he attended, he made an impression. “He had this really dry sense of humor,” said Bette Maisel, a friend from California. “He was already 35 . . . He was like this old Jewish comedian.”

In Orem, Utah, he was the person all the younger kids tried to imitate, said Drew Brown, a classmate. And with such sensitive social antennae, Carter seemed to know when someone needed encouragement or praise. In English class one day, the students were asked to write about someone who influenced them.

“And Carter wrote about me,” said Brown, still touched by the gesture. “I was writing about my favorite athlete — and Carter wrote about me.”

So it was typical of Carter, in 2005, to extend his sympathy in an online memorial to a fellow male student who left school — and never returned. “If I could give you one thing, it would be a second chance, because you are a great person with a great heart, and I know that it’s hard sometimes, but as I’m learning, we just have to keep on working,” Carter wrote on an online obituary guest book. “I know [you’re] up there now watching over everyone you knew and loved. Wish you were still here.”

At age 14, Carter had seen firsthand how opioids had crept into his generation’s world: the schoolmate was found at home, in his closet, having overdosed on heroin.

Home for Christmas from Landmark College in Vermont, Carter had surgery to remove a benign tumor from his lower back. Because of complications — the surgical site tore open and had to be closed again with a drain — he was first prescribed a regimen of pain medication through a patch applied to his arm.

His mother said she learned much later that a doctor, despite being informed of Carter’s genetic susceptibility to addiction, prescribed a fentanyl patch, a synthetic opioid that is at least 40 times stronger than morphine.

Doctors at Columbia University told her that triggered an opioid dependency, and ultimately led to his first detox and subsequent rehabilitation in 2011. (Carter’s father, Eugene, said other opioid painkillers taken during that period, prescribed by perhaps more than one doctor, might have ultimately led to his heroin use.)

Carter had endured other issues before, including ADHD and an anxiety disorder, but this was a challenge of a different magnitude. It pushed him over a cliff, and he spent the rest of his life trying to claw back.

It’s the nature of addiction that you fall, stand up and fall down again. (Often again and again.) The year 2013 seems to have started well for Carter — at least that’s the public face he presented. In March, he announced on Facebook that he was starting a job at the family bus company in the Hudson Valley. (“. . . first day of work tomorrow . . . and I’m PUMPED!!”).

But by that autumn, he had fallen again, discovered by his brother Alex, about to use. It meant a local hospital for detox, and then the beginning of a second rehab stint, this one in Connecticut.

By Christmas that year, he had had more than two months of sobriety, and sat down to write a note — a son to his mother.

Sailing at the Vineyard Haven Yacht Club. Martha’s Vineyard was always a refuge for Carter, who came every summer. — Courtesy Berardi family

He was also sharing his hopes for a productive life ahead. Ms. Sullivan, his friend dating back so many summers on the Vineyard, visited him in rehab where they shared their struggles and dreams. “He wanted to help out people with substance abuse issues, and help them get better,” she said. “And that to me was hopeful — he was talking about the future.”

Carter spent about three months in rehab in facility in northwestern Connecticut and was released. After a quick trip home to the Hudson Valley to pick up a car, phone and belongings, he moved into a sober living house, in what is usually an appropriate transition for those early in recovery, between the cocoon of rehab and the “regular” world. He entered the sober house on Thursday, Jan. 9. Three days later, a Sunday, he was discovered in his locked room, slumped over his laptop, dead of “acute heroin intoxication,” according to the police report.

There had been warning signals. In text messages and phone calls, he had expressed some concern about the safety of the place. By Saturday, Liz wanted to come pick him up. Carter told her he would call her the next day, and that he had arranged to go back into rehab.

“I waited,” she said. “And waited. And waited.” His call never came.

Carter’s father said he had been in touch by phone, including Sunday morning, the day Carter died, and promised to visit him Monday. “That’s the last conversation I had with him,” he said. That evening, a police officer was waiting at his home to deliver the news that Carter was gone.

“I can tell you, he was a sort of gentle giant, a great kid. I loved him dearly and was proud of him,” Mr. Berardi said.

An extended police investigation into the source of the drugs appears inconclusive, and police aren’t sure whether the drugs were in the sober house or might have been obtained by Carter right after leaving rehab.

At his memorial service the following Saturday at the Old Dutch Church in Kingston, N.Y., friends spoke of their memories of Carter, among them Ms. Sullivan.

“It’s impossible to sum up Carter; his personality was infinite . . .” she said during the service. “He expected the best from you and built you up to be the best version of yourself. He made me a better person . . .”

Liz Berardi has moved to the Vineyard full time, where a sign in her driveway greets visitors to Three Boy Hill. She has started a nonprofit called Safe Sober Living, which advocates for those fighting substance abuse. And she joined an effort in the Hudson Valley to address the opioid crisis, the Ulster (County) Coalition Against Narcotics.

She continues to talk about what she considers an inadequate safety net, from doctors overprescribing painkillers to a lack of parity in insurance coverage for people in recovery, as well as lack of safety standards for sober houses. She’s heartened by a surge of awareness about these issues.

Liz Berardi, Carter’s mother, lives full time on the Vineyard and has started a nonprofit to bring the stigma of addiction out into the open. — Jeanna Shepard

In Massachusetts, the state has imposed seven-day limits on initial opioid prescriptions, set up an online prescription monitoring system to discourage “doctor shopping” and encouraged medical and dental schools to beef up their curricula to include addiction and appropriate pain treatment.

On the Island, a working group representing a diverse cross section of the community meets regularly to address the needs in fighting and treating substance abuse. And online and newspaper obituaries appear to be more frequently mentioning a loved one’s struggles with substance abuse.

Yet even with the passage of time, Carter’s loss remains unfathomable to family and friends.

“Carter could be a pain, but I still wish, every day, he were here,” said his brother Alex. “He loved his family and he loved his friends so much. The last thing he ever would have wanted was to hurt us, or hurt any one. He just couldn’t overcome it.

“I wish we could have all known sooner so that we could have lent a better hand,” he added.

Those who knew and loved Carter see him as another reason to bring the struggles of the addicted out of the closet, all the better to address it and treat it. Morgan Hawley, one of Carter’s mentors at his school in Utah, has lost other friends to substance abuse.

“Everyone thinks it’s their own dirty secret,” Hawley said. “But as humans, we’re more alike in the struggles we’re going through. We think it’s a big scarlet letter.

“But everyone wears a scarlet letter; some of us just hide it better.”

–

Original article can be found here:

https://vineyardgazette.com/news/2016/10/13/losing-boy-next-door-working-shatter-stigma